|

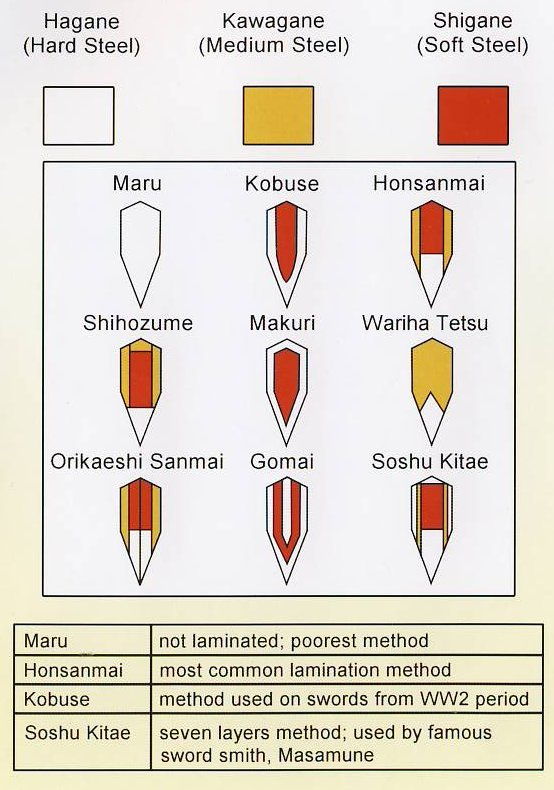

Let us read a little about katana before diving on sword sharpening at the bottom. Historically, katana (刀) were one of the traditionally made Japanese swords (日本刀 nihonto) that were worn by the samurai class of feudal Japan, also commonly referred to as a "samurai sword". Modern versions of the katana are sometimes made using non-traditional materials and methods. If mishandled in its storage or maintenance, the katana may become irreparably damaged. The blade should be stored horizontally in its sheath, curve down and edge facing upward to maintain the edge. It is extremely important that the blade remain well-oiled, powdered and polished, as the natural moisture residue from the hands of the user will rapidly cause the blade to rust if not cleaned off. The traditional oil used is choji oil (99% mineral oil and 1% clove oil for fragrance). Similarly, when stored for longer periods, it is important that the katana be inspected frequently and aired out if necessary in order to prevent rust or mold from forming (mold may feed off the salts in the oil used to polish the katana). The authentic Japanese sword is made from a specialized Japanese steel called "Tamahagane" which consist of combinations of hard, high carbon steel and tough, low carbon steel. There are benefits and limitations to each type of steel. High-carbon steel is harder and able to hold a sharper edge than low-carbon steel but it is more brittle and may break in combat. Having a small amount of carbon will allow the steel to be more malleable, making it able to absorb impacts without breaking but becoming blunt in the process. The makers of a katana take advantage of the best attributes of both kinds of steel. The maker begins by folding and welding pieces of high and low carbon steel several times to work out most of the impurities. The high carbon steel is then formed into a U-shape and a billet of soft steel is placed in its center. The resulting block of steel is then drawn out to form a rough blank of the sword. At this stage it is only slightly curved or may have no curve at all. The gentle curvature of a katana is attained by a process of quenching; the sword maker coats the blade with several layers of a wet clay slurry which is a special concoction unique to each sword maker, but generally composed of clay, water, and sometimes ash, grinding stone powder and/or rust. The edge of the blade is coated with a thinner layer than the sides and spine of the sword, then it is heated and then quenched in water (some sword makers use oil to quench the blade). The clay slurry provides heat insulation so that only the blade's edge will be hardened with quenching and it also causes the blade to curve due to reduced lattice strain along the spine. This process also creates the distinct swerving line down the center of the blade called the hamon which can only be seen after it is polished; each hamon is distinct and serves as a katana forger's signature. When steel with a carbon content of 0.7 percent is heated beyond 750 degrees C it enters the "austenite phase". When austenite is cooled very suddenly by quenching in water the structure changes into "martensite", which is an extremely hard form of steel. When austenite is allowed to cool slowly its structure changes into a mixture of ferrite and pearlite which is softer than martensite. By carefully controlling the heating and cooling of the blade being forged Japanese swordsmiths were able to produce a blade that had a softer body and a hard edge creating a superior weapon, this process is called differential hardening or differential quenching. The reason for the formation of the curve in a properly hardened Japanese blade is that iron carbide, formed during heating and retained through quenching, has a lesser density than its root materials have separately. After the blade is forged it is then sent to be polished. The polishing takes between one and three weeks. The polisher uses finer and finer grains of polishing stones until the blade has a mirror finish in a process called glazing. This makes the blade extremely sharp and reduces drag, making it easier to cut with. The blade curvature also adds to the cutting power. Sword Sharpening Be very careful when sharpening katana. Please don't think about sharpening a sword that could be a valuable heirloom. You could be destroying an irreplaceable piece of history and costing yourself hundreds of thousands. A Practical Katana or rusty gunto is a good place to start. Practicing with 2000 grit or finer stones makes it harder to destroy the geometry of the blade, but you should expect to destroy the first blades you try to sharpen.

Nihonzashi LLC, its employees, and associated companies are not responsible for any injury, damage or loss incurred by following any advice given on this site. Katana are dangerous objects and the utmost care should be given when working with them. Grit The first thing everyone asks is what grit stones are used to polish or sharpen a sword. What could be easier than selecting grit? Is that US, European, English, or Japanese grit? Grit specified the mesh used to separate the abrasive particles, but everyone uses a different standard and they don't compare well. Things really fall apart at the finer grits since the US standard switches from grit to particle size in microns. The following table will give you some clues on how to relate the different standards. From this point I will use the Japanese grit since I use Japanese water stones graded by this standard. Equivalent Grit Table

Japanese Water Stones Japanese water stones are either natural or artificial. Natural stones can be quite expensive, but artificial stones can be used for sharpening polish. About half the stone used in a full cosmetic polish can also be artificial, but some steps require specific natural stones. Artificial stones use a graded abrasive suspended in either a clay or ceramic media. The stones use water as a lubricant. Even the inexpensive stones can run $50 each. Soaking the Stones Japanese water stones need to be soaked in water to work properly. Stones take from 5 to 20 minutes to become saturated depending upon the stone. While some stones can be stored in water others must be stored dry. I store all my stones dry and soak them for 20 minutes to simplify things. I put about a quarter cup of sodium bicarbonate in the water. Baking soda will change the pH of the water and keep your sword from rusting while you are sharpening it. Some stones like those from Debado should not be soaked but simply sprinkled with water before using. These stones will deteriorate if soaked. Shaping the Stones Japanese water stones constantly wear down during use. This is normal and helps maintain an aggressive cutting surface. Some stones wear down quite quickly while other stones are quite stable. Stones used to sharpen a sword should be slightly convex and have rounded corners. The stones will become concave (hollowed out) during use so they should be reshaped before or after each use. Special stones are available for keeping your stones true, but I just use each stone to flatten the next finer grit stone when I switch grits. Keeping the edges rounded or beveled will keep the stone from fracturing and help keep you from grinding a grove in your blade. Sharpening Base Being a westerner with a bad back, I sharpen swords standing. I use a custom wood platform on my workbench to secure the stones to. Some stones are already attached to bases, and I use one of those standard rubber bases for unmounted stones. You need a sturdy platform that stands up to the water. I used a platform that fit over the kitchen sink when I was single, but a couple of buckets for water keep me out of trouble now. You might prefer clamping down your stones and base, but I find it is unnecessary. Straightening the Blade You might have to straighten the blade before you sharpen it. This is your last chance. Once you start sharpening, the geometry will be lost. Straightening a sword is an art in itself. The simplest method but hardest to master is simply bending it over your knee after sighting down it's length. There are slotted wood sword straightening tools available that allow you to isolate the bend easier. Whatever method you choose, just remember to take your time. Getting a Grip The sword should be disassembled and the bare blade sharpened. Even the habaki should be removed. I use a piece of an old towel about 1x1 foot wrapped around the blade to provide a good grip. It has to be tight so it does not slide (and slice). When I'm working the monouchi I use my right hand to grip the sword and my left hand to counter the weight of the sword and steady the kissaki. Be careful of slipping your left hand off the blade or you could loose a few fingers. Make sure to wipe off any oil. I use two pieces of towel to grip the sword with both hands when working on other parts of the blade. Remember that it is easy to cut yourself badly when sharpening a sword. Sharpening The blade should pass over the stone using a uniform even stroke. This is polishing and not grinding! I use both the forward and backward movement to do the work. Go slow and inspect the blade often. Don't worry about how the edge feels. Just make sure you have worked the stone over the entire surface of the blade while maintaining the surface geometry. A good light source is essential to seeing where you have missed. Remember that you are not sharpening the edge. You are removing metal until the edge is exposed. Scratch Pattern The first stone should be used until the scratch pattern just reaches the edge. The only exceptions are when removing chips or when the edge has been flattened. The geometry should be established with the coarsest stone and subsequent stones should just refine the surface. The angle of the scratch pattern of each stone can be varied to make sure all the scratches from each stone are removed by the next. Holding the blade up to the light will reveal scratches from previous stones cutting across the pattern. Cosmetic polishes alternate the pattern by 90 degrees to make sure every scratch is removed. Leave the Edge The most common mistake is paying too much attention to the edge. All your attention should be on the surface of the blade. The surfaces must be removed to reveal the edge. The first stone is key. The surfaces should be worked until the scratch pattern reaches the edge while maintaining the desired surface geometry. You must keep working with the first stone until the scratch pattern reaches the edge. There may be only a very thin polished surface that reflects the light, so look very carefully. If the edge has been flattened or chipped, you need to continue past this point. 100 Strokes Once I have established the geometry with the coarsest stone, I use 100 strokes of each stone on both sides of the blade to refine the surface. I use long strokes that cover about 15 inches of blade. I find the geometry comes out more uniform this way. That also means that the entire monouchi can be covered in a single stroke. The blade is rotated very slightly to cover the entire surface from the shinogi to ha. Rounding the Shinogi It is key to not round over the shinogi. This is the line that runs down the length of the blade delineating the cutting surface. The blade will need to be worked right up to the shinogi line, but it is very easy to turn the blade too much and destroy the geometry of the blade. The blade has a tendency to roll over and round the shinogi due to its curvature. You can hear when the stone is working the shinogi or ha. The tone of the scraping changes slightly as you reach the edge. Be careful! Lubrication Slurry is formed on the top of the stone as it breaks down. This paste acts as a lubricant and as an abrasive. The stone needs to be periodically re-wetted. Use water with dissolved baking soda to keep the stone wet. Don't wash the paste off the stone. Use your hand to dip water onto the stone and keep the blade clean. A small rag can be used, but be careful not to leave thread or other pieces of debris on the stone or blade. You will need to switch water when you switch stones or the coarse grit in the water will leave scratches in the blade. The finer stones need to have a paste formed with a nagura stone to work properly. The nagura stone is soaked with the water stones and rubbed on the top of the finish stones to form a paste. Power Tools The worst thing you can possible do is using a belt sander, orbital sander, or grinder on your sword. That is the fastest possible way to turn that sword into junk. Power tools can quickly remove the temper or destroy the geometry of the blade. Orbital sanders destroy the geometry by rounding over the ha and shinogi. I use Delta and Makita wet grinders to reshape badly chipped blades, but they need allot of practice to use. The grinding wheels move slow and are water cooled so the blade does not heat up. Abrasive Paper Some people use progressively finer grits of silicon carbide sandpaper to sharpen swords. I have no problem with that, but I personally don't use that method. I'll keep my water stones and let others do their own thing. You can get silicon carbide and diamond lapping film that covers the same abrasive grit range as Japanese water stones. Jigs You can get a wide variety of sharpening systems designed for knifes. These jigs have one big problem. They are all intended to create an edge with a single angle. A katana should have a slightly curved continuous surface from the ha to shinogi. It is not a big knife and can not be sharpened like one. You can get more data about the geometry of a katana by checking out the edge geometry

0 Comments

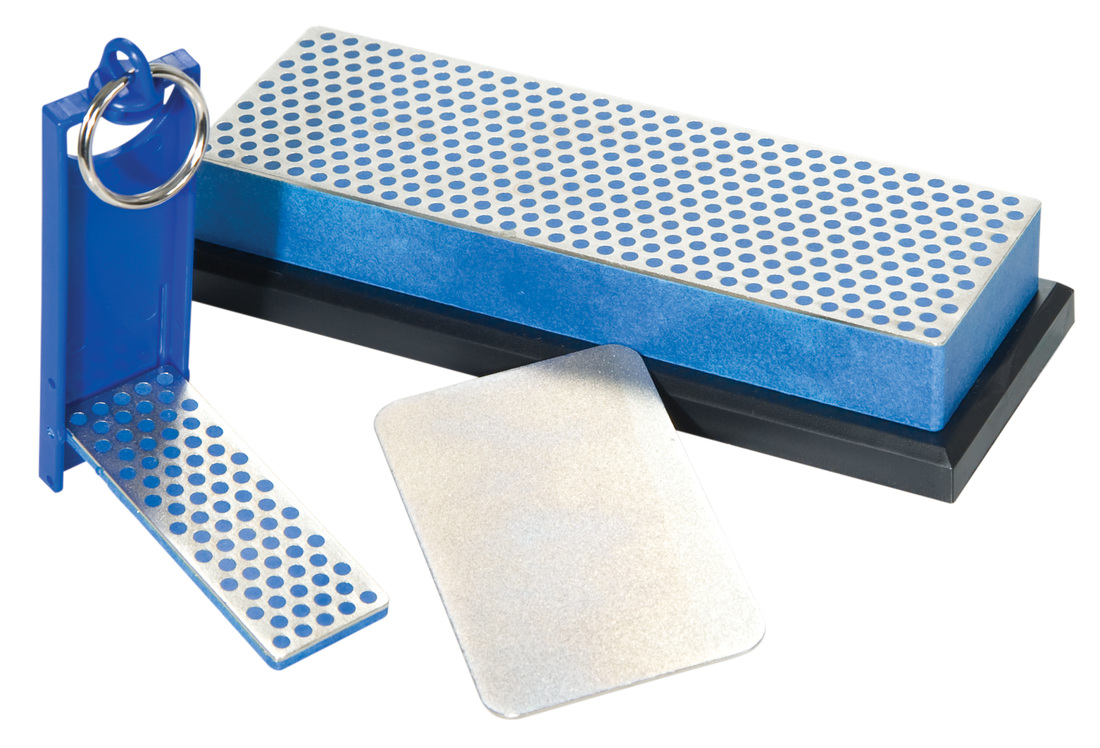

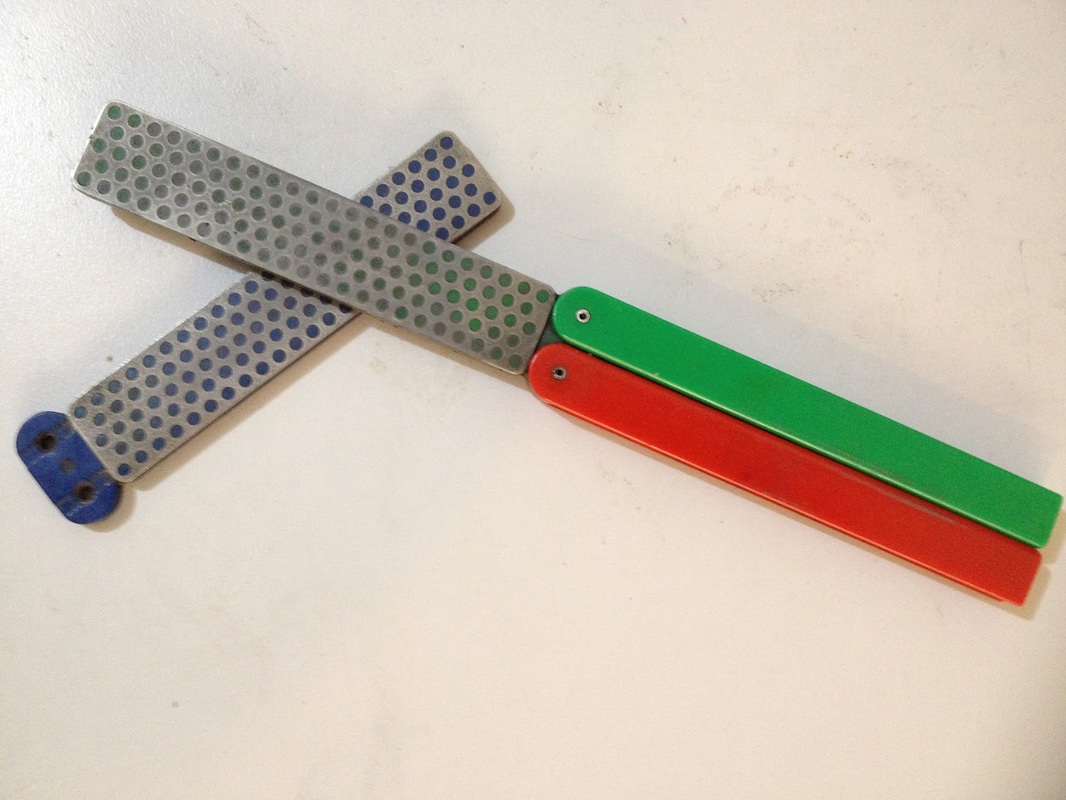

Below is a good read about sharpening written by Joe Talmadge. Translucent Arkansas Stone and Black Arkansas Stone are the finest natural sharpening stones known to man. For thousands of years man has used Arkansas natural stone (novaculite) as knife sharpening stone. These fine sharpening stones prolong the life of your blade because they don't remove large amounts of metal from your blade like some electric systems. Our rare locally mined, Arkansas stones will polish the edge of your knife while you sharpen. These Arkansas knife sharpening stones are made of different grades of Novaculite- hard, compact, homogenous, finely granular, highly pure silica rock mined only in Arkansas. There are three stones on a Tri-Stone: one course, one medium, and one fine. All Tri-Stones include a bottle of honing oil, angle guide and 'How To Use Sharpening Stones' instructions. "How to sharpen a knife." Diamond Stones are the finest "synthetic" sharpening stones. Check out the good read below.... The Sharpening FAQs from the Usenet News Group rec.knives

Author: Joe Talmadge [email protected] The KnifeCenter of the InterNet presents this text as a service to our browsing public and make no claims as to its accuracy or efficacy. Some parts have been modified by the KnifeCenter. I. Introduction When I started writing this FAQ, I began by writing a detailed treatise on how to sharpen. I soon found that there was no way I could do this in the kind of detail I wanted without ending up with a book-length FAQ. As it turns out, someone has already written a book on sharpening, and done a better job than I could have done. So the most important part of this FAQ, for the beginner, is the following recommendation: the first thing you need to do is buy and read _The Razor Edge Book of Sharpening_ by John Juranitch. No matter what sharpening system you end up using, the fundamentals as laid out by Juranitch remain intact. I don't agree with Juranitch on everything, but the illustrations he gives really help with understanding the principles. So this FAQ will discuss the central elements of sharpening, and then go on to more detailed subjects. Sharpening angles, hones, sharpening systems, the latest fads in edges (e.g., chisel grinds), etc. Basically, Juranitch will show you how to get a burr and grind it off to end up with a sharp knife. Hopefully, the FAQ will tell you everything else. For many people, when they try to sharpen a knife, the knife actually gets duller! If it's any consolation, I was in the same boat at one time. The best way to start out is to read about the sharpening fundamentals, and then use some kind of sharpening system (discussed below) that pre-sets the angles. That way, you can begin by learning how to raise a burr, feel for the burr, and then grind it away, without having to worry about keeping the angle consistent as well. When you understand how to sharpen, then you can get rid of the rig, buy some flat hones, and learn how to sharpen freehand. II. The Fundamentals of Sharpening - Getting a Sharp Edge Okay I lied about not discussing the sharpening ritual itself. Here's a much-too-short review of the sharpening process, before we get into the rest of the FAQ. If this section is confusing, read _The Razor Edge Book of Sharpening_. Many of the subjects in this section (e.g., stone grits) are explored further elsewhere in the FAQ. You grind one edge along the stone edge-first until a burr (aka "wire") is formed on the other side of the edge. You can feel the burr with your thumb, on the side of the edge opposite the stone. The presence of the burr means that the steel is thin enough at the top that it is folding over slightly, because the bevel you've just ground has reached the edge tip. If you stop before the burr is formed, then you have not ground all the way to the edge tip, and your knife will not be as sharp as it should be. The forming of the burr is critically important -- it is the only way to know for sure that you have sharpened far enough on that side. Once the burr is formed on one side, turn the knife over and repeat the process. To re-cap, you've sharpened one side only until you felt a burr along the entire length of the opposite side, then you switched sides and repeated the process. I suggest you do not follow the directions that come with many sharpeners, of the form "Do 20 strokes on one side, then 20 strokes on the other". You go one side only until the burr is formed; if that takes 10 strokes or 50 strokes, you keep going until you get a burr, period. Only then do you flip the knife over and do the other side. Having raised a burr, our job now is to progress to finer stones, in order to make the edge smoother and remove the burr. So now we run the blade along the stone from end to tip, this time alternating sides with each stroke. Switch to a finer stone, and then do it again. Sometimes, the burr is turned directly downwards during sharpening, and since it is very thin and razor sharp, it seems like an incredible edge. This is called a "wire edge". But being fragile, it will break off the very first time you use the knife, leaving you with an extremely dull knife. If you seem to be getting good sharpening results on your knives, but they are getting dull very quickly with little use, you may be ending up with a wire edge. If that's the case, you'll need to be careful and watch out specifically for a wire edge; you should try progressing down to finer stones, try double-grinding the edge, and give the knife a quick stropping once you're finished (all these terms are explained below). If your knife is fading fast as you're sure it's not because you left a wire edge, steeling between uses may be what you need. My last few strokes on the stone become progressively lighter, to avoid collapsing the edge and raising another burr. On a badly-worn or damaged edge, I'll typically start with a medium (300-400 grit) stone, then move to a fine (600 grit) stone, and then sometimes I'll finish on an extra-fine (1200 grit) stone if I want a more polished edge. However, once my knife is sharp I try to re-sharpen before it gets too worn down. In that case, I can usually start on the fine stone. But be sure to read the important notes on grits later in the FAQ. Lastly, I may use a leather strop on the knife. On other sharpening systems, the same fundamentals as laid out above still apply. For example, on a V-type sharpener, I'll start by sharpening one side only against the right-hand stick until a burr forms. Then I switch to the other stick until a burr forms. Only after I've raised a burr from both sides will I follow the manufacturer's directions and alternate from one stick to the other between strokes. What Angle? The smaller the angle, the sharper your knife will feel. But the smaller the angle, the less metal that's behind the edge, and thus the weaker the edge. So your sharpening angle will depend on your usage. A surgeon's blade will have a very thin, very low-angle edge. Your axe will have a strong, thick, high-angle edge. Something like a razor blade will having an angle of around 12- degrees, and it's chisel-ground so that's 12-degrees total. Utility knives will have angles anywhere between 15- and 24- degrees (30-48 degrees total). An axe will have something around a 30-degree angle. For double-ground utility knives, a primary edge of 15-18-degrees, followed by a secondary grind of 21ish-degrees, works well. Don't be obsessed with getting the exact right angle; rather, make sure that at whatever angle you've chosen, concentrate on holding it precisely. See also the sections on convex edges and chisel-ground edges. - What Kind of Stone? Basically, a stone needs to cut metal off the edge. The stones below do this well, and for most of us our time would be better spent actually learning how to sharpen than worrying too much about the minor advantages of one stone vs. another. Get the biggest stones you can afford and have room for. Big stones make the job much much easier. The time-honored stone is the arkansas stone. Soft arkansas stones provide the coarser grits, with harder stones providing finer grits. Many people use oil on these stones, ostensibly to float the steel particles and keep them from clogging the stone. John Juranitch has popularized the notion that oil should absolutely not be used when sharpening, and indeed results from people using arkansas stones without oil have been very positive. However, if you have ever used oil on your arkansas stone, you need to continue using it, or it will clog. If you never put oil on your arkansas stone, you will never need to. Synthetic stones are very hard, and won't wear like natural stones (a natural stone may get a valley scooped out of it over time). They clean well with detergent-charged steel wool, I use SOS detergent pads, they clean very very fast and very well. I know you're thinking that cleaning with steel wool will cause the stone to shear off the steel wool and fill up the stone even worse! But I assure you that is not the case, for whatever reason SOS pads clean synthetic stones, they do not make the stones dirtier. Spyderco and Lansky are some manufacturers who sell synthetic stones. Stones with diamond dust embedded in them cut aggressively. You can remove metal very quickly if you need to, but be careful lest you remove too much too fast! DMT, Eze-Lap, and Lansky are some manufacturers who sell diamond-based hones. Some diamond stones have the problem that the diamond dust wears off quickly, leaving you with a useless stone. I have experience with the DMT stones, and can say that they do not have this problem. Natural stones will eventually dish out in the center with use. To flatten them back out, put some sandpaper on a flat surface and rub the stone top on it. Wet/dry 400 grit sandpaper mounted on a table top or glass is reputed to work well. - Should I Use Water or Oil on My Stone John Juranitch has popularized the notion that no liquid should be used on the sharpening stone. Since oil has been used for many years on stones, this leads to some confusion. Basically, the purpose of the stone is to rub against the blade and remove metal. Slippery liquids, like water and especially oil, make the rubbing slicker, causing less metal to be removed, causing sharpening to take longer. On top of that, Juranitch claims that as your edge is being sharpened on the stone, the oil-suspended metal particles are washing over the edge and dulling it again. On an arkansas stone, the oil is supposedly needed to float metal particles away from the stone surface, lest the stone clog and stop cutting. Some people on this group have used their arkansas stones without oil or water, and have reported good results. However, if you've already used oil on your arkansas stone, you'll probably need to keep using oil forever on it, because an already-oiled stone will clog up if not kept oiled. If you have a fresh arkansas stone, go ahead and use it without the oil, and things should be okay. I've used diamond and synthetic stones without liquid, and they worked just fine. In any case, the bottom line is: use liquid or don't. Using the liquid will make the sharpening process slower and messier, but if you insist on using liquid and are willing to spend more time, that's your call. If you don't have the skill to hold a consistent angle, it's all moot anyway! - How Fine Should My Stone Be? Important notes on grits! The finer the stone, the more polished your edge will become. The rougher the stone, the more the scratches in the edge function as "micro-serrations". Though the actual ontological status of the micro-serrations is debatable (Juranitch says there's no such thing, having looked under a microscope), the serrated effect of the coarser grind is undoubtably there. The more polished the edge, the better your edge will work for doing push-cut applications like shaving, whittling, peeling an apple, skinning a deer. Also, your cut will be more clean and precise with the polished edge. A rougher, more micro-serrated edge will work better for slicing-type applications like cutting through coarse rope, wood, etc. The serrations present more edge surface area, and tend to "bite" into the thing being cut. It is possible to get an edge that will shave hair with a medium (300-400 grit) stone, with practice [I specifically mention stone grits because many manufacturers call the 300-400 grit stones "coarse" rather than "medium"]. The medium stone will have pretty big micro-serrations. In previous version of the FAQ I stated that I find this too rough a finish for my general utility edge. However, I've since found this to be a really nice edge finish for utility work -- it won't shave great, but it does a really nice job on cutting coarse materials. Anyone should be able to get an edge that shaves hair easily with a fine (600 grit) stone. I find this to be a pretty useful finishing stone, leaving enough micro-serrations for general utility work but still being hair-shaving sharp. An extra fine stone (1200 grit) should start polishing the edge, and you should end up with a hair-popping sharp edge. This is also a good choice for a general utility finish, especially on a partially-serrated blade, where the serrations can be used when the slightly-polished main part of the blade becomes less effective. ************ IMPORTANT TIP **************** Many treatises on sharpening tend to focus on getting a polished, razor-like edge. This is partially the fault of the tests we use to see how good our sharpening skills are. Shaving hair off your arm, or cutting a thin slice out of a hanging piece of newpaper, both favor a razor polished edge. An edge ground with a coarser grit won't feel as sharp, but will outperform the razor polished edge on slicing type cuts, sometimes significantly. If most of your work involves slicing cuts (cutting rope, etc.) you should strongly consider backing off to the coarser stones, or even a file. This may be one of the most important decisions you make -- probably more important than finding the perfect sharpening system! Recently, Mike Swaim (a contributor to rec.knives) has been running and documenting a number of knife tests. Mike's tests indicate that for certain uses, a coarse-ground blade will significantly outperform a razor polished blade. In fact, a razor polished blade which does extremely poor in Mike's tests will sometimes perform with the very best knives when re-sharpened using a coarser grind. Mike's coarse grind was done on a file, so it is very coarse, but he's since begun favoring very coarse stones over files. The tests seem to indicate that you should think carefully about your grit strategy. If you know you have one particular usage that you do often, it's worth a few minutes of your time to test out whether or not a dull-feeling 300-grit sharpened knife will outperform your razor-edged 1200-grit sharpened knife. The 300-grit knife may not shave hair well, but if you need it to cut rope, it may be just the ticket! If you ever hear the suggestion that your knife may be "too sharp", moving to a coarser grit is what is being suggested. A "too sharp" -- or more accurately, "too finely polished" -- edge may shave hair well, but not do your particular job well. Even with a coarse grit, your knife needs to be sharp, in the sense that the edge bevels need to meet consistently. - Stropping Stropping consists of running the edge along a piece of leather charged with some kind of abrasive like stropping paste or green chromium oxide (I had previously said jeweler's rouge is okay, but have since heard that a more aggressive cutter is needed). It is done for a short time to finish off the burr, or for a long time to give the edge a final polish. Stropping is an easy-to-use finishing step (as opposed to the difficulty in keeping a consistent angle on a stone). Before you strop, remember to wash and dry your newly-sharpened knife. If you don't, you might grind leftover metal particles into the strop itself. If you need to charge your strop, put a little paste on your fingers and rub it into the leather. To strop, you run the edge along the leather with the blade positioned spine first and the edge trailing (opposite way from sharpening on a stone). With a thin straight razor, the spine of the razor is always kept on the strop, and direction is switched by flipping the razor over along its spine. In my experience, this isn't necessary with a utility knife. You can strop with the blade spine raised above the leather (don't lift too high -- if the edge bites into the leather, that's too high), and change directions by lifting the entire knife up, turning it over, and placing it back down. If you've never stropped your knife before, give it a try. It will come out very sharp, but of course polished and so optimized for push-type shaving cuts. The strop to some extent can make up for less-than-perfect sharpening technique -- a sharp knife can be made extra sharp on the easy-to-use strop. However, I always tell people that they should be able to get their knife scary sharp without the strop; don't let the strop keep you from recognizing weaknesses and improving your technique on the hone! In the absence of a strop (say, out in the field), many people use their jeans and then their palm as a strop. There's probably no need to point out the danger in this practice, so don't do it. That said, I must admit to having done this myself on numerous occasions, and having gotten good results. A safer and more effective trick is to use cardboard (say, the cardboard back of a standard notepad). You can optionally charge the cardboard with metal polish, just rub it in with your fingers. Then strop as above. Even without the polish, the cardboard will strop acceptably. Stropping with cardboard has become a de-facto standard last step for sharpening chisel-ground (single-side ground) knives these days, for burr removal purposes. - Using a Steel Please see our instruction page for steels HERE The sharpening steel should be an important part of your knife maintenance strategy, and is maybe the most mis-understood part. When you use a knife for a while, especially a knife with a soft, thin edge like that found on a kitchen knife, the edge tends to turn a bit and come out of alignment. Note that the edge is still reasonably sharp, but it won't feel or act very sharp because the edge may not point straight down anymore! At this point, many people sharpen their knives, but sharpening is not necessary and of course decreases the life of the knife as you sharpen the knife away. It's also akin to putting in a thumbtack with a sledgehammer. The steel is used to re-align the edge on the knife. Read that last sentence again. Re-aligning the edge is all the steel needs to do. It does not need to remove any metal. Since the steel's only function is to re-align, the sharpening steel can be perfectly smooth and still do its job. You'll see many bumpy steels on the market, but this is almost certainly because consumers think that steels must have bumps to work. The bumps can actually mess up the edge, and make the work of steeling more difficult. There are two schools of thought on steels. Some people use grooved steels, which align the edge more aggressively but are harder on the edge. I use a smooth steel, which is easy on the edge but may align the edge more slowly. To use the steel, run the knife along the steel on one side using light pressure -- no more pressure than the actual weight of the knife is required! Then switch to the other side and do it again. Repeat a number of times until your edge feels sharp and nice again. I hold the steel in my left hand, the blade in my right, and lightly run the blade along the steel while keeping the steel stationary, but it's perfectly fine to move both steel and knife past each other at the same time, or whatever works for you. Most people run the knife down the steel edge first, the same direction you use when sharpening. This yields good results. However, theoretically going edge-first along the steel could bite into the edge while straigtening it, and so many people like to go spine-first (like when stropping) instead. This method also works well, and I personally have begun to feel that steeling in this direction gets my edge the tiniest bit sharper. It is more awkward to go spine-first, so if you have any trouble with it switch to edge-first, and your edge will end up just fine. If you steel your knife every time you use it, you will significantly lengthen the time between sharpenings. I've found steeling to be critical on kitchen knives, but it's an incredible help even on ultra-hard ATS-34. III. Putting it all together - Some tips and tricks If you want to determine if you are sharpening at the same angle that the blade already has, try this easy trick. Mark the edge bevel with a magic marker. Then go ahead and do a stroke or two on the stone (or take a stroke with your Lansky, or whatever). Now pick the knife up and look at the edge. If you have matched the edge angle exactly, the magic marker will be scraped off along the entire edge bevel. If your angle is too high, only the marker near the very very tip will be gone. If your angle is too low, only the marker near where the edge bevel meets the primary bevel will be gone. Another trick is to use light and shadow to get the edge precisely. Using strong directly light, lay the edge down on the stone and watch the shadow below. As you tilt the spine up, the edge contacts more of the stone and the shadow disappears. As the shadow just disappears and the edge just touches the stone, that's your angle. If you go higher than that, you should be able to see the edge tilting over onto the stone. One trick to freehand sharpening is to use your thumb as a guide. I'll place the spine of the blade against my thumb pad, and rest my thumb on the stone. That way, I can feel the angle between the knife and stone, and make sure that it is consistent. Typically, the hardest part to freehand sharpen is the curving belly of the blade, as keeping a consistent angle here is more difficult. I use all these tricks extensively when sharpening freehand, and use the marker trick even when I'm using a sharpening rig. One thing to keep in mind is that there's no reason you need to keep the factory edge. If you're happy with that edge, great. However, many factory edges are too thick to really cut well. If you're unhappy with the cutting ability of your knife, don't be afraid to try lowering the angle a bit. - Why does my knife go dull so fast? A frequent complaint I hear is, "I sharpened my knife and did a good job, it was really sharp. But then after just a few uses it went dull." Why does this happen? One of the following factors -- and many times a combination of those factors -- is at play: 1. Wire edge If the burr is not properly ground off, but is instead turned downwards, your knife will feel razor sharp. However, the burr quickly turns or snaps off, leaving you with a very dull-feeling knife. Be sure to use a light touch at the end of the sharpening process and make sure the burr is gone. 2. Thin, weak edge If the bevel angle you chose for your knife is too thin for your usage, the edge can chip and get really wavy. Try using a larger edge angle, or at least double-grinding the edge. 3. Edge turning In regular use, all edges turn to some extent. If your edge is much too thin, it will be damaged as above in #2. If it's only slightly too thin, it will quickly turn out. As long as the the edge is not being damaged, but simply turning, you don't necessarily need to re-grind a thicker edge. Instead, see if frequent steeling will give you the performance you need, it can really work wonders. Keep in mind it's difficult to see a turned-out edge by eyeball -- only using the steel will tell you conclusively if this is your problem. 4. Thick edge A thin edge will feel sharper than a thick edge. If your edge is too thick, when it starts to dull even the slightest bit it may no longer feel so sharp anymore. Consider using a lower angle and seeing if that helps. Of course, your thinner edge will be more fragile than the thicker edge, so you may end up chipping the edge out, and the thinner edge may not be feasible. I personally feel that this is rarely the real problem, so be sure to try the other solutions first. 5. Soft steel Occasionally, a manufacturer or maker will make a mistake while heat treating, and the steel in the blade will end up too soft. No matter how well you sharpen, your blade will still go dull quickly. Often, soft steel is the first thing people point at when their edges dull quicker than expected. But this problem really is relatively rare; in the vast majority of cases, it is one of the above reasons rather than soft steel that's the problem. So if your edge dulls too fast, don't blame the steel until you've exhausted the above options. If it's still dulling quickly, contact the manufacturer, they are often interested in testing to see if they made a mistake. - Keeping bevels even With the burr method of sharpening, one side of the knife can end up with more metal taken off it than the other side. This forces the edge to be not-quite-centered. This normally doesn't affect performance, but aesthetically it doesn't look quite right. This happens because as you grind the one side to create the bevel, it has to go far (that is, lots of metal has to be removed) to create the bevel on the other side. When you flip to the other side, the edge is already thin, so very little metal has to be removed to flop the burr back over. There are a few ways to avoid this. First, you can just switch which side you start sharpening on. If you start with the edge that's on the right side of the blade, that edge bevel will be a little bigger than the one on the left side. So next time you sharpen, start off on the left side. You can pick which side to start your sharpening on by just using whatever side seems to have a smaller edge. The method I use is to switch sides while trying to get the initial burr. If I start on the right side, I'll sharpen for 20 seconds or so and then check for a burr. If no burr is found, I switch to the left side and repeat. I keep doing this -- sharpening one side for a time, then the other side -- until I finally start to feel a burr. Then I just follow the normal directions: I keep sharpening that side until the burr goes the entire length of the edge, then flip and get a burr along the entire length of *that* edge. The fact that I'm flipping the knife keeps the edge bevels even. - Putting it all together As you use your knives, you may see your sharpening strategies change. Many of us seem to be homing in on the philosophy that you should choose the thinnest, coarsest edge possible that can do your job without the edge being damaged, especially in the context of general usage. Thin blades and low-angle edges seem to cut better than thick ones. They slide through the material being cut with less effort. Which makes sense -- the wider the V that your edge forms, the more metal you're pushing into the material. However, go too thin and your edge can chip out. So go as thin as you can without damaging your edge, and use a steel often to touch it up. Obviously, what "thin" means depends on usage. "Thin" means one thing when the job is slicing soft materials, something else entirely when chopping hard materials. Lightly double-grinding a shallower bevel on a thin edge may help give you the best of both worlds. If your first bevel is a thin 15-degrees (say), try doing a few light finishing strokes at a stouter 24-degress. Coarser edges slice better than polished ones, but a polished edge will laterally push-cut (e.g., shave) better. If you find yourself doing a lot of lateral push cuts, then you'll obviously want to polish your edge more. However, most people do much more slicing than push cutting, and as a result end up with a much more polished edge than optimal. You should play around with coarser grits. The edge won't do as well shaving hair, but unless this particular knife is a razor blade, who cares? You may find the knife cutting through other materials much better than usual. Lastly, I have become something of a steel fanatic. Steeling your knife frequently -- even if the blade is of really high-hardness steel -- works wonders on the edge. It also allows you to have a slightly thinner (and hence better-cutting) edge, because if you steel frequently you'll keep the edge aligned. If you don't steel at all, you'll have to use an edge that's thick enough not to turn, and that may negatively affect sharpness and cutting power. Remember to steel frequently, because if your edge's shape gets too bad, the steel won't work and you'll have to go back and sharpen. Know any good knife sharpening tips or tecniques you would like to pass on to others? We'd be happy to hear them- simply click here to e-mail them to us. |

Categories

All

Archives |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed