|

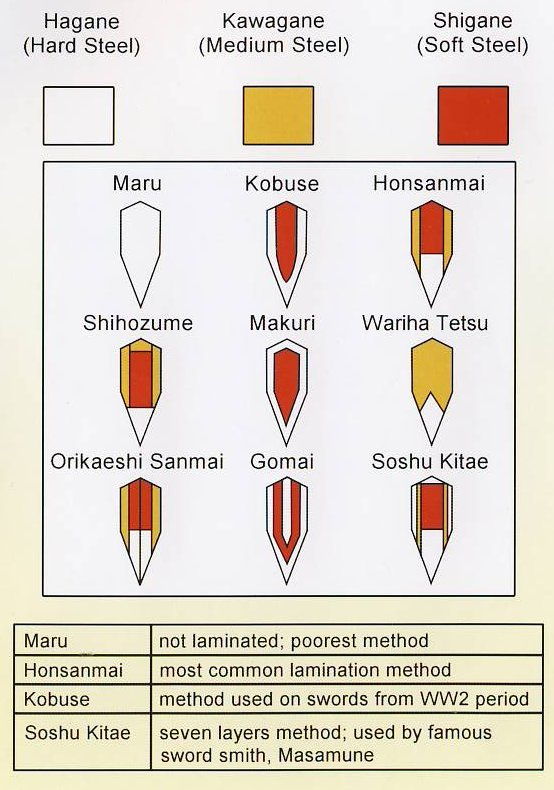

Let us read a little about katana before diving on sword sharpening at the bottom. Historically, katana (刀) were one of the traditionally made Japanese swords (日本刀 nihonto) that were worn by the samurai class of feudal Japan, also commonly referred to as a "samurai sword". Modern versions of the katana are sometimes made using non-traditional materials and methods. If mishandled in its storage or maintenance, the katana may become irreparably damaged. The blade should be stored horizontally in its sheath, curve down and edge facing upward to maintain the edge. It is extremely important that the blade remain well-oiled, powdered and polished, as the natural moisture residue from the hands of the user will rapidly cause the blade to rust if not cleaned off. The traditional oil used is choji oil (99% mineral oil and 1% clove oil for fragrance). Similarly, when stored for longer periods, it is important that the katana be inspected frequently and aired out if necessary in order to prevent rust or mold from forming (mold may feed off the salts in the oil used to polish the katana). The authentic Japanese sword is made from a specialized Japanese steel called "Tamahagane" which consist of combinations of hard, high carbon steel and tough, low carbon steel. There are benefits and limitations to each type of steel. High-carbon steel is harder and able to hold a sharper edge than low-carbon steel but it is more brittle and may break in combat. Having a small amount of carbon will allow the steel to be more malleable, making it able to absorb impacts without breaking but becoming blunt in the process. The makers of a katana take advantage of the best attributes of both kinds of steel. The maker begins by folding and welding pieces of high and low carbon steel several times to work out most of the impurities. The high carbon steel is then formed into a U-shape and a billet of soft steel is placed in its center. The resulting block of steel is then drawn out to form a rough blank of the sword. At this stage it is only slightly curved or may have no curve at all. The gentle curvature of a katana is attained by a process of quenching; the sword maker coats the blade with several layers of a wet clay slurry which is a special concoction unique to each sword maker, but generally composed of clay, water, and sometimes ash, grinding stone powder and/or rust. The edge of the blade is coated with a thinner layer than the sides and spine of the sword, then it is heated and then quenched in water (some sword makers use oil to quench the blade). The clay slurry provides heat insulation so that only the blade's edge will be hardened with quenching and it also causes the blade to curve due to reduced lattice strain along the spine. This process also creates the distinct swerving line down the center of the blade called the hamon which can only be seen after it is polished; each hamon is distinct and serves as a katana forger's signature. When steel with a carbon content of 0.7 percent is heated beyond 750 degrees C it enters the "austenite phase". When austenite is cooled very suddenly by quenching in water the structure changes into "martensite", which is an extremely hard form of steel. When austenite is allowed to cool slowly its structure changes into a mixture of ferrite and pearlite which is softer than martensite. By carefully controlling the heating and cooling of the blade being forged Japanese swordsmiths were able to produce a blade that had a softer body and a hard edge creating a superior weapon, this process is called differential hardening or differential quenching. The reason for the formation of the curve in a properly hardened Japanese blade is that iron carbide, formed during heating and retained through quenching, has a lesser density than its root materials have separately. After the blade is forged it is then sent to be polished. The polishing takes between one and three weeks. The polisher uses finer and finer grains of polishing stones until the blade has a mirror finish in a process called glazing. This makes the blade extremely sharp and reduces drag, making it easier to cut with. The blade curvature also adds to the cutting power. Sword Sharpening Be very careful when sharpening katana. Please don't think about sharpening a sword that could be a valuable heirloom. You could be destroying an irreplaceable piece of history and costing yourself hundreds of thousands. A Practical Katana or rusty gunto is a good place to start. Practicing with 2000 grit or finer stones makes it harder to destroy the geometry of the blade, but you should expect to destroy the first blades you try to sharpen.

Nihonzashi LLC, its employees, and associated companies are not responsible for any injury, damage or loss incurred by following any advice given on this site. Katana are dangerous objects and the utmost care should be given when working with them. Grit The first thing everyone asks is what grit stones are used to polish or sharpen a sword. What could be easier than selecting grit? Is that US, European, English, or Japanese grit? Grit specified the mesh used to separate the abrasive particles, but everyone uses a different standard and they don't compare well. Things really fall apart at the finer grits since the US standard switches from grit to particle size in microns. The following table will give you some clues on how to relate the different standards. From this point I will use the Japanese grit since I use Japanese water stones graded by this standard. Equivalent Grit Table

Japanese Water Stones Japanese water stones are either natural or artificial. Natural stones can be quite expensive, but artificial stones can be used for sharpening polish. About half the stone used in a full cosmetic polish can also be artificial, but some steps require specific natural stones. Artificial stones use a graded abrasive suspended in either a clay or ceramic media. The stones use water as a lubricant. Even the inexpensive stones can run $50 each. Soaking the Stones Japanese water stones need to be soaked in water to work properly. Stones take from 5 to 20 minutes to become saturated depending upon the stone. While some stones can be stored in water others must be stored dry. I store all my stones dry and soak them for 20 minutes to simplify things. I put about a quarter cup of sodium bicarbonate in the water. Baking soda will change the pH of the water and keep your sword from rusting while you are sharpening it. Some stones like those from Debado should not be soaked but simply sprinkled with water before using. These stones will deteriorate if soaked. Shaping the Stones Japanese water stones constantly wear down during use. This is normal and helps maintain an aggressive cutting surface. Some stones wear down quite quickly while other stones are quite stable. Stones used to sharpen a sword should be slightly convex and have rounded corners. The stones will become concave (hollowed out) during use so they should be reshaped before or after each use. Special stones are available for keeping your stones true, but I just use each stone to flatten the next finer grit stone when I switch grits. Keeping the edges rounded or beveled will keep the stone from fracturing and help keep you from grinding a grove in your blade. Sharpening Base Being a westerner with a bad back, I sharpen swords standing. I use a custom wood platform on my workbench to secure the stones to. Some stones are already attached to bases, and I use one of those standard rubber bases for unmounted stones. You need a sturdy platform that stands up to the water. I used a platform that fit over the kitchen sink when I was single, but a couple of buckets for water keep me out of trouble now. You might prefer clamping down your stones and base, but I find it is unnecessary. Straightening the Blade You might have to straighten the blade before you sharpen it. This is your last chance. Once you start sharpening, the geometry will be lost. Straightening a sword is an art in itself. The simplest method but hardest to master is simply bending it over your knee after sighting down it's length. There are slotted wood sword straightening tools available that allow you to isolate the bend easier. Whatever method you choose, just remember to take your time. Getting a Grip The sword should be disassembled and the bare blade sharpened. Even the habaki should be removed. I use a piece of an old towel about 1x1 foot wrapped around the blade to provide a good grip. It has to be tight so it does not slide (and slice). When I'm working the monouchi I use my right hand to grip the sword and my left hand to counter the weight of the sword and steady the kissaki. Be careful of slipping your left hand off the blade or you could loose a few fingers. Make sure to wipe off any oil. I use two pieces of towel to grip the sword with both hands when working on other parts of the blade. Remember that it is easy to cut yourself badly when sharpening a sword. Sharpening The blade should pass over the stone using a uniform even stroke. This is polishing and not grinding! I use both the forward and backward movement to do the work. Go slow and inspect the blade often. Don't worry about how the edge feels. Just make sure you have worked the stone over the entire surface of the blade while maintaining the surface geometry. A good light source is essential to seeing where you have missed. Remember that you are not sharpening the edge. You are removing metal until the edge is exposed. Scratch Pattern The first stone should be used until the scratch pattern just reaches the edge. The only exceptions are when removing chips or when the edge has been flattened. The geometry should be established with the coarsest stone and subsequent stones should just refine the surface. The angle of the scratch pattern of each stone can be varied to make sure all the scratches from each stone are removed by the next. Holding the blade up to the light will reveal scratches from previous stones cutting across the pattern. Cosmetic polishes alternate the pattern by 90 degrees to make sure every scratch is removed. Leave the Edge The most common mistake is paying too much attention to the edge. All your attention should be on the surface of the blade. The surfaces must be removed to reveal the edge. The first stone is key. The surfaces should be worked until the scratch pattern reaches the edge while maintaining the desired surface geometry. You must keep working with the first stone until the scratch pattern reaches the edge. There may be only a very thin polished surface that reflects the light, so look very carefully. If the edge has been flattened or chipped, you need to continue past this point. 100 Strokes Once I have established the geometry with the coarsest stone, I use 100 strokes of each stone on both sides of the blade to refine the surface. I use long strokes that cover about 15 inches of blade. I find the geometry comes out more uniform this way. That also means that the entire monouchi can be covered in a single stroke. The blade is rotated very slightly to cover the entire surface from the shinogi to ha. Rounding the Shinogi It is key to not round over the shinogi. This is the line that runs down the length of the blade delineating the cutting surface. The blade will need to be worked right up to the shinogi line, but it is very easy to turn the blade too much and destroy the geometry of the blade. The blade has a tendency to roll over and round the shinogi due to its curvature. You can hear when the stone is working the shinogi or ha. The tone of the scraping changes slightly as you reach the edge. Be careful! Lubrication Slurry is formed on the top of the stone as it breaks down. This paste acts as a lubricant and as an abrasive. The stone needs to be periodically re-wetted. Use water with dissolved baking soda to keep the stone wet. Don't wash the paste off the stone. Use your hand to dip water onto the stone and keep the blade clean. A small rag can be used, but be careful not to leave thread or other pieces of debris on the stone or blade. You will need to switch water when you switch stones or the coarse grit in the water will leave scratches in the blade. The finer stones need to have a paste formed with a nagura stone to work properly. The nagura stone is soaked with the water stones and rubbed on the top of the finish stones to form a paste. Power Tools The worst thing you can possible do is using a belt sander, orbital sander, or grinder on your sword. That is the fastest possible way to turn that sword into junk. Power tools can quickly remove the temper or destroy the geometry of the blade. Orbital sanders destroy the geometry by rounding over the ha and shinogi. I use Delta and Makita wet grinders to reshape badly chipped blades, but they need allot of practice to use. The grinding wheels move slow and are water cooled so the blade does not heat up. Abrasive Paper Some people use progressively finer grits of silicon carbide sandpaper to sharpen swords. I have no problem with that, but I personally don't use that method. I'll keep my water stones and let others do their own thing. You can get silicon carbide and diamond lapping film that covers the same abrasive grit range as Japanese water stones. Jigs You can get a wide variety of sharpening systems designed for knifes. These jigs have one big problem. They are all intended to create an edge with a single angle. A katana should have a slightly curved continuous surface from the ha to shinogi. It is not a big knife and can not be sharpened like one. You can get more data about the geometry of a katana by checking out the edge geometry

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Archives |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed